Siyuan Xie

UC Berkeley

Alper Gel

UC Berkeley

Ryan Arlett

UC Berkeley

Sihan Ren

UC Berkeley

Link to this webpage | slides | video

Abstract

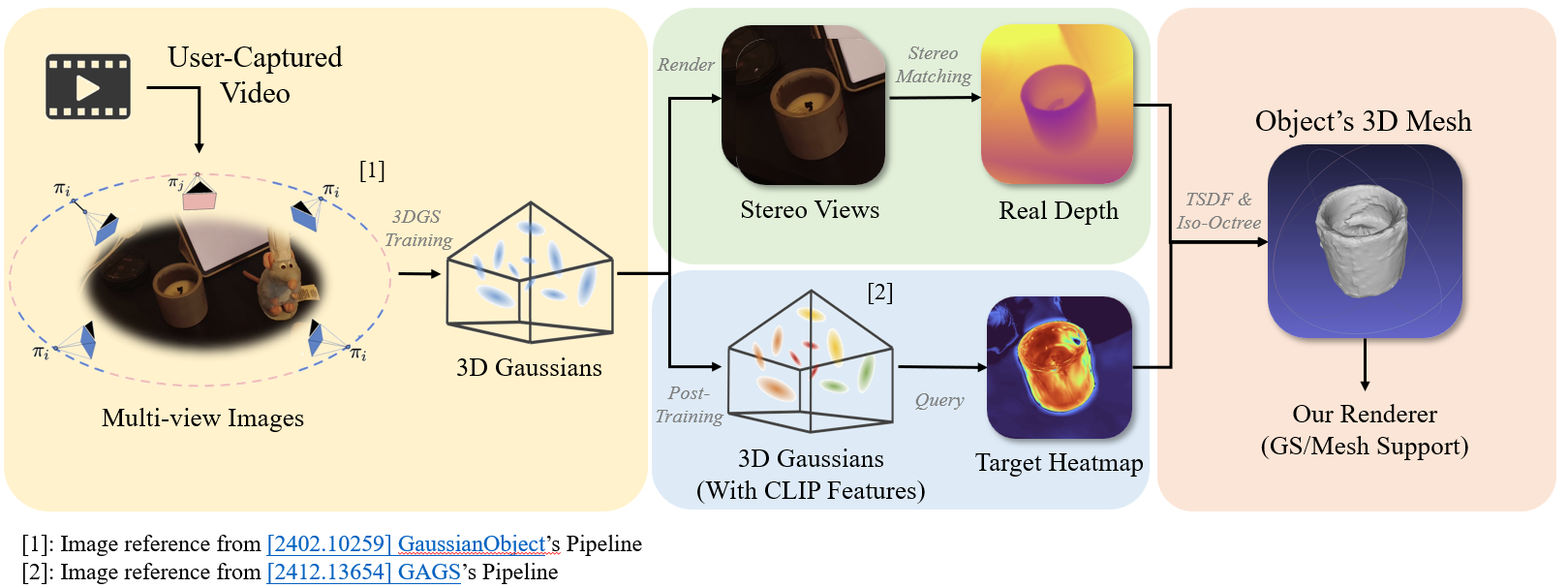

We have developed a pipeline that extracts high-quality meshes of user-specified objects from an input video. Our approach builds upon 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), a powerful method for accurate scene reconstruction. While Gaussian splats serve as an implicit geometric primitive, converting them into explicit mesh representations to enable compatibility with modern industrial pipelines remains challenging. Existing approaches like SuGaR and GS2Mesh often suffer from poor surface quality and undesirable object adhesion, which significantly limits their practicality.

Our pipeline works in several stages: First, we convert video into a Gaussian Splatting scene, then isolate specific objects based on text input through a semantic-aware segmentation strategy. For this, we leverage a post-training process to augment the Gaussian scene with semantic information, resulting in a semantically enriched point cloud. Based on the text query, we render consistent multi-view depth maps and semantic masks.

After the objects are separated, we utilize an improved mesh reconstruction algorithm guided by local point density via a state of the art Stereo-Matching model. We apply TSDF fusion in conjunction with an Iso-Octree structure to adaptively extract high-quality meshes from the masked depth regions, overcoming the limitations of previous approaches.

Finally, to visualize our results, we’ve implemented a custom DirectX11-based renderer capable of displaying both the extracted meshes and the intermediate Gaussian splatting scenes for comparison. Our pipeline combines existing GS libraries (for video-to-GS conversion and object separation) with our own algorithms for mesh reconstruction and rendering.

Related Works

Gaussian Splatting and Volume Rendering

Recent advances in neural rendering have proposed numerous techniques for efficient scene representation and novel-view synthesis. Volumetric approaches such as NeRF model the scene as a continuous radiance field, rendering images via volumetric ray marching. Specifically, the color $C$ of a pixel is computed as:

$$ C = \sum_{i=1}^{N} T_i \alpha_i c_i $$

The transmittance $T_i$ is defined as $T_i = \prod_{j=1}^{i-1} (1 - \alpha_j)$, and the opacity is given by $\alpha_i = 1 - \exp(-\sigma_i \delta_i)$, where $\sigma_i$ and $\delta_i$ denote the density and interval length at the $i$-th sample, respectively.

While this formulation provides high fidelity, it requires dense and costly sampling per ray. In contrast, point-based and Gaussian splatting methods use discrete primitives projected directly onto the image plane. Each 3D Gaussian is defined by a position, an anisotropic covariance matrix, and a view-dependent color, often represented via spherical harmonics. When projected to 2D, these Gaussians are rasterized using alpha blending with visibility ordering, leading to the same image formation model as NeRF, but with $\alpha_i$ derived from the projected 2D Gaussian opacity. This enables real-time rendering and efficient training by avoiding expensive ray marching, while retaining the continuous nature and high quality of volumetric representations through a compact set of explicit 3D Gaussians.

Spatial Language Embedding

Recent work has extended 3D Gaussian Splatting to encode semantic and language-aligned information into radiance fields. LangSplat introduces a mechanism to supervise each 3D Gaussian with CLIP-derived embeddings extracted from training views. To achieve this, high-dimensional CLIP features ($\mathbb{R}^{512}$) are first compressed into a lower-dimensional latent space ($\mathbb{R}^d$) using a scene-adaptive autoencoder.

For each semantic level (subpart, part, whole), LangSplat learns view-specific latent targets via reconstruction. Each 3D Gaussian is assigned a learnable embedding $f_i^l \in \mathbb{R}^d$, rendered into views using alpha-composited splatting. The rendered semantic map is defined as:

$$ F_t^l(v) = \sum_{i \in \mathcal{N}(v)} f_i^l \cdot \alpha_i \cdot \prod_{j=1}^{i-1}(1 - \alpha_j) $$

where $\alpha_i$ denotes the opacity of the $i$-th Gaussian and $\mathcal{N}(v)$ is the set of Gaussians overlapping pixel $v$. Supervision is provided by minimizing the discrepancy between projected features and the ground-truth latent embeddings:

$$ \mathcal{L_{\text{lang}}} = \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{l \in {s, p, w}} \text{dist}(F_t^l(v), H_t^l(v)) $$

where the target feature $H_t^l(v)$ is the compressed CLIP embedding at that same pixel and level. Training aligns rendered and target features. This design enables per-Gaussian language conditioning and view-consistent semantic representations, allowing downstream applications such as natural language querying and part segmentation.

Method

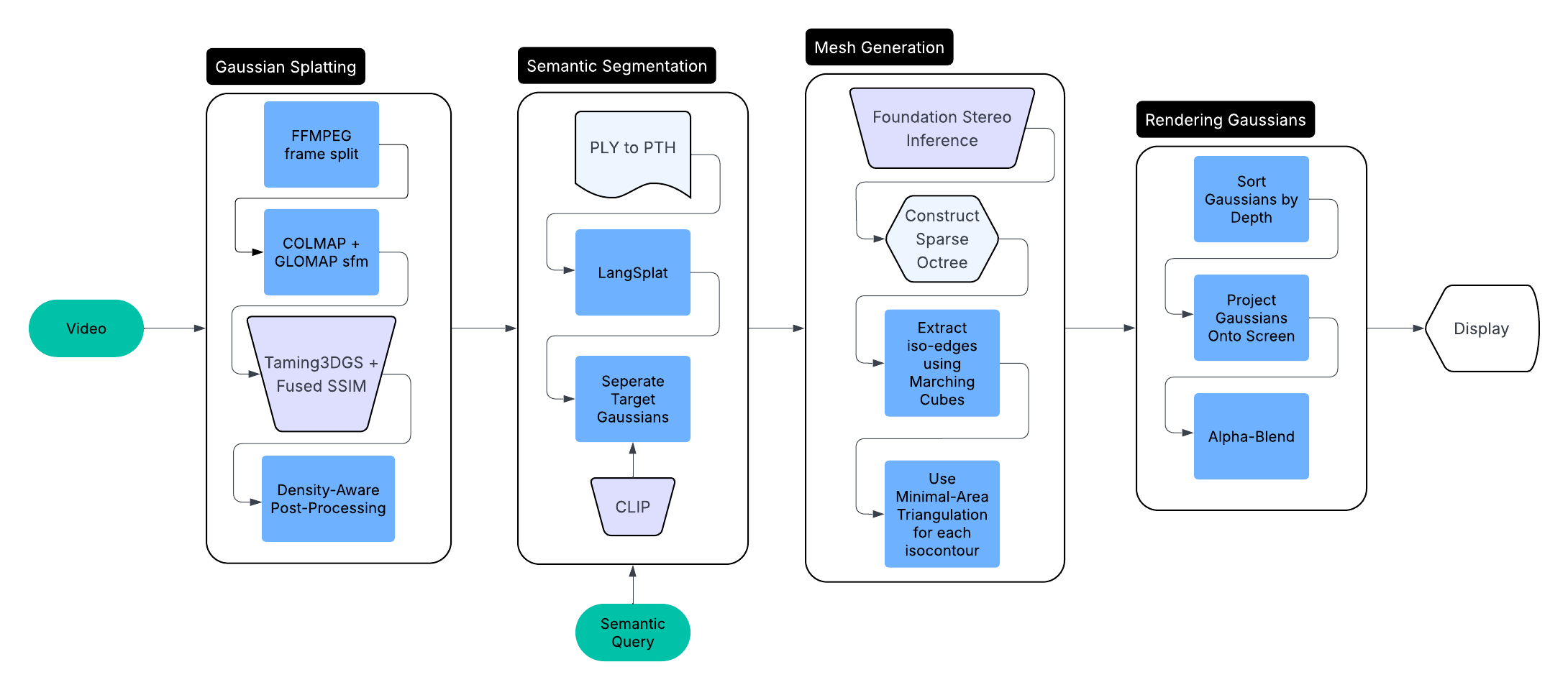

We decompose the overall pipeline into four subtasks: (1) 3DGS-based scene reconstruction, (2) semantic information extraction from the optimized Gaussian points, (3) depth estimation guided by text input, and (4) mesh extraction from masked depth maps using TSDF and iso-octree fusion.

Gaussian Splatting for Accurate Reconstruction

Our pipeline begins by converting the input video into a Gaussian Splatting scene. To achieve this, we first sample the video at 2 fps, and only select the sharpest frames using a variety of OpenCV functions. Next, we run SIFT-GPU + COLMAP feature extraction followed by COLMAP matching [7][13]. Finally, to optimize for speed, we utilize GLOMAP’s mapper to complete the SFM process [8]. These functions combined allow for a 3D reconstruction of the camera poses, giving the SFM precursor that gaussian splatting requires. During training, we utilize the Taming-3DGS + Fused SSIM accelerated rasterization engine to achieve sub 20-minute training times on consumer GPU’s (RTX 4070 mobile) [12].

Since we are building off of the Gaussian-Splatting-Lightning library, our work here entailed compiling seamless docker pipelines via docker-compose where the script calls the relevant docker container, runs the code required, and exits moving on to the subsequent task [6]. This allows any computer, with any OS to run our code, given they have an NVIDIA CUDA powered GPU. Overall, the goal of our work in this segment was to bring together existing libraries to create a seamless, robust, and quick video to gaussian splat pipeline, that can be easily utilized for subsequent pipeline stages.

Example input video, output gaussian splatting scene (rendered in our own DirectX11 Renderer)

Language-Driven Semantic Query/Visualization

To support natural language interaction with 3D representations, we propose a two-stage pipeline centered around image-space query and visualization, with an optional extension for extracting semantic 3D Gaussians based on prompt alignment.

Stage 1: Per-View Query and Visualization

Our core pipeline enables language-based visualization by operating on latent semantic features extracted from each training view. Specifically, we first decode per-pixel features $F_t$ from each view $t$ into the CLIP-aligned embedding space using a trained decoder $\Psi$, obtaining:

$$ \hat{F}_t = \Psi(F_t) \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times D} $$

Given a set of textual prompts ${p_k}$, we compute a similarity score for each pixel:

$$ S_t^{(i,j,k)} = \text{sim}(\hat{F}_t^{(i,j)},; \phi(p_k)) $$

Here, $\phi(p_k)$ denotes the CLIP embedding of prompt $p_k$. The similarity maps are smoothed via local averaging and normalized, followed by thresholding with $\tau$ to produce binary masks:

$$ M_t^{(k)} = \mathbb{1}[S_t^{(k)} > \tau] $$

Among all CLIP attention heads, we select the one with the highest global response for each prompt to generate the final visualization. The system outputs per-prompt heatmaps, binary masks, and composite visual overlays. This stage is implemented via the activate_stream() and text_query() routines, and supports tasks such as semantic segmentation, text-guided editing, and interactive inspection of the 3D scene from 2D projections.

Stage 2 (Optional): Prompt-Guided 3D Gaussian Extraction

As an alternative or complementary step, we offer a method to extract subsets of 3D Gaussians that consistently correspond to a given prompt across multiple views. Each 3D point $x_i$ is projected into the image plane of view $t$ via:

$$ x_{i,t}^{2D} = \pi_t(x_i) = \mathbf{K}_t \left( \mathbf{R}_t x_i + \mathbf{t}_t \right) $$

A point receives a binary vote if its projection falls inside the activated mask $M_t^{(k)}$ and passes a depth consistency check with rendered depth $D_t$:

$$ z_i < D_t(x_{i,t}^{2D}) \cdot (1 + \epsilon) $$

We accumulate votes across all views and select points that are activated in at least $V$ images:

$$ \text{mask}_k(i) = \mathbb{1} \left[ \sum_{t=1}^{T} M_t^{(k)}(\pi_t(x_i)) \geq V \right] $$

This yields a prompt-specific semantic subset of Gaussians, saved as a new PLY file. This extended module supports occlusion filtering, resolution control, and enables downstream applications like phrase-conditioned subcloud editing or text-guided mesh extraction.

For this component, work also went towards pipelining it to work with our other components, in addition to fitting it within the Docker build infrastructure. Once this was complete, our group updated the CLIP model utilized from the OpenCLIP library, due to the out-of-date model choices of the LangSplat library [11]. As a further note for the reader, LangSplat utilizes the antiquated Segment-Anything-Model (SAM), which is significantly slower and produces worse segmentations than the recently released SAM 2.1 model series [2]. Due to this, a significant amount of our time for this stage was spent attempting to upgrade the SAM model, but due to a major difference in model inference infrastructure, and library configuration mismatches, we were unable to complete this upgrade.

Stereo Matching

In parallel with the segmentation process, we also obtain high-quality depth estimates of the scene via iterative stereo matching. In short, the stereo matcher uses the difference in object positions between two renders with slightly shifted camera positions to compute depth. For each training view, we artificially translate the gaussian view camera slightly rightword, and render a second image using the same 3DGS scene representation. Since we know each image from this process is aligned along the baseline, they can be reliably fed into a stereo matching model to compute a dense depth map. When picking the right model to perform the stereo-matching process, we opted to utilize NVIDIA’s state-of-the-art FoundationStereo model, given its recent release and significant advances. This model robustly yields accurate depth predictions from rectified stereo image pairs [4].

Initially we attempted to use DepthAnythingV2, which is a monocular (single-view) depth estimation model, but these models produce pseudo-depths bounded between $[0, 1]$ that are unsuitable for precise 3D reconstruction, proven through our initial noisy outputs. Further, due to the inherent noise in the Gaussian surfaces of 3DGS, we avoid computing depth directly from the expected volume density, since this also produced unstable results based on our preliminary testing. Instead, our stereo-based pipeline yields metrically accurate and globally consistent depth maps that can be reliably used by our mesh generation algorithm.

Mesh Reconstruction

Finally, we extract a geometrically accurate mesh from the rendered heatmaps, depth maps, and associated camera parameters. We begin by masking the depth maps using the heatmaps to suppress irrelevant regions, setting those areas to zero. These masked depths are then fused into a continuous signed distance field using a Truncated Signed Distance Function (TSDF) integration scheme.

To build the TSDF field, we evaluate the signed distance between each voxel center and its projections in all training views. Let $x \in \mathbb{R}^3$ be a voxel center and let $D_t$ be the depth map of view $t$. The signed distance at $x$ is computed as:

$$ \text{TSDF}_t(x) = \frac{D_t(\pi_t(x)) - | x - c_t |}{\delta(x)} $$

where $\pi_t(x)$ is the projection of $x$ onto the image plane of camera $t$, $c_t$ is the camera center, and $\delta(x)$ is the truncation distance—adaptively chosen based on projected depth or clamped to a global maximum $\delta_{\text{max}}$.

Only pixels with valid depth estimates contribute to the TSDF. The per-voxel TSDF value is computed by weighted averaging across views:

$$ \text{TSDF}(x) = \frac{\sum_t w_t(x) \cdot \text{TSDF}_t(x)}{\sum_t w_t(x)} $$

Here, the weight $w_t(x)$ is inversely proportional to the projected depth, favoring closer observations:

$$ w_t(x) = \frac{1}{| x - c_t | + \epsilon} $$

We discard large negative TSDF values in voxels that fall behind observed surfaces, as these typically correspond to occluded or non-visible regions. To prevent reconstruction holes due to insufficient valid observations, we assign a fallback value of $-1$ to voxels that are consistently behind surfaces in multiple views.

This fusion strategy avoids relying on surface normals, enabling compatibility with noisy or unstructured input depth maps. The resulting TSDF field is continuous, normalized, and suitable for iso-surface extraction.

To achieve both high extraction efficiency and adaptive mesh resolution, we adopt the classic IsoOctree method [10]. This approach hierarchically partitions space using an octree structure, enabling efficient focus on regions where the signed distance function (SDF) exhibits sign changes. Furthermore, the method can condition on point cloud density to support spatially adaptive resolution control.

Specifically, we first construct a sparse octree where each node stores TSDF values at its voxel corners. For each voxel edge, we then build an associated edge-tree, a binary structure that encodes the multi-resolution sign-change status along that edge. If an edge contains a zero-crossing, we recursively traverse its edge-tree to identify the finest sub-edge containing the crossing, and interpolate the SDF values to obtain a well-defined isovertex:

$$ \text{isovertex} = \text{lerp}(x_a, x_b;, \frac{\text{TSDF}(x_a)}{\text{TSDF}(x_a) - \text{TSDF}(x_b)}) $$

For each leaf node in the octree, we extract iso-edges from its six faces using a marching squares–style algorithm. When a face borders a finer-resolution neighbor, we copy the precomputed iso-edges from the finer node to ensure boundary consistency. To prevent open surfaces, we check all isovertices with valence one and trace their symmetric counterparts through the edge-tree to form twin connections, closing any incomplete iso-contours.

Ultimately, every iso-edge is shared by exactly two faces, guaranteeing that the resulting mesh is both watertight and manifold. Each closed isocontour (isopolygon) is then triangulated using a minimal-area triangulation strategy to form the final triangle mesh.

This method enables consistent and high-fidelity mesh extraction from an unconstrained octree without requiring node refinement or vertex updates, achieving a balance between detail preservation and spatial sparsity.

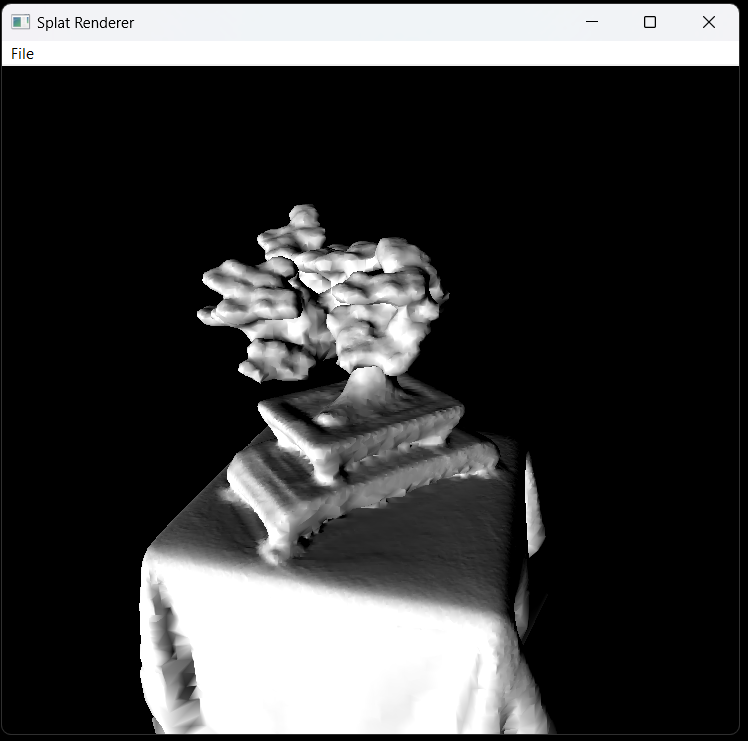

GS&Mesh Viewer

To view our results (both the intermediate Gaussian Splatting scenes and our output meshes), we created a DirectX11 based windows application from scratch that can render both .PLY (GS) and .OBJ (Mesh) files.

For our starting point, we began with an empty visual studio project, and the only starter code we used was a math helper file (containing classes for vectors, quaternions, and matrices) written by Ryan for a past project. The vertex shader code in [16] was also very helpful later on as a reference, although we ended up writing a slightly different one ourselves.

Our first task was to get a simple windows application up with a menu bar to select files and keyboard input handling for camera movement. As Ryan had prior experience with the Windows graphics API, this process was relatively seamless. After that, we wrote a function to parse an input .PLY file to extract the Gaussians (positions, colors, opacity, rotations and scales), and calculate the Gaussians covariance matrices as RSSTRT as described in [14]. From there we sorted all the gaussians based on depth. During this process, the gaussians’ positions are first transformed by the camera’s view matrix to find the depth, then sorted using the standard library std::sort.

Next, for our first attempt at rendering the scene, we looped through each Gaussian, in order, alpha blending them onto the screen. This meant, for each Gaussian, projecting its position and scales into clip space. For simplicity, for now we ignored rotation, both of the camera and of gaussians, and just treated them as axis aligned 2D gaussian blobs with the projected x and y scale components as their standard deviations. Finally, we loop through every pixel on the screen, calculating the gaussians alpha value at that pixel’s position on clip space using the standard equation for a gaussian distribution, and alpha blend the gaussians color onto the pixel based on the calculated alpha value. Though this ignored the rotations of the gaussians and the camera, it still gave somewhat decent results, considering most Gaussians were fairly spherical. It also ran very slowly (~1 fps), as everything was being done on the CPU. This is what we had done by our milestone, and is how we generated our milestone images.

At this point we decided to switch to DirectX11, as we were already in effect performing a vertex shader on each Gaussian (projecting to clip space), then a pixel shader to blend each pixel, so the algorithm lended itself naturally to the GPU. For this transition the DirectX sample projects were helpful [9] to get the necessary setup right.

Now, properly handling the rotations involves complicated math as described in [15], so here we decided to find a reference solution to help. We found a WebGL based GS renderer [16], which helped immensely with the math in our vertex shader described below. The main difference between our implementation and this reference solution is that they draw instanced quads, passing the quad into the vertex shader, then get the Gaussian data for that quad by sampling a texture, and then do the math to find the correct position and rotation for the quad.

Instead, our renderer passes the Gaussian data directly into the vertex shader, then generates the rotated quad by using a geometry shader in between the vertex and pixel shaders. This seems to us like the more natural way to do it, and avoids packing and unpacking the data through a texture. It also means the math in the vertex shader is done only once per Gaussian, instead of 4 times for each vertex of that Gaussian’s quad. Our final GS rendering process is described below:

- Initialize the windows app and DirectX

- Parse input .PLY file and put Gaussian data (positions, colors, covariance matrices) into vertex buffer on GPU.

- Spawn background CPU thread to asynchronous sort Gaussians, and flag main thread to update GPU vertex buffer when done.

- Tell DirectX to render the Gaussian data using our shaders below

- Vertex Shader: (Takes in per-gaussian data)

- Project position to clip space using camera view and projection matrices

- Project Covariance matrix to clip space using camera view matrix and the affine approximation of the projection matrix. Now have a 2D covariance matrix representing a 2D gaussian in clip space.

- Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of this matrix. If you think of the 2D gaussian as a rotated ellipse the major/minor axes are the eigenvectors scaled by their eigenvalues. Pass these “major/minor axes” to the Geometry shader.

- Geometry Shader: (Takes in output of vertex shader)

- Generate a rotated quad (two triangles) to surround this 2D gaussian. Spans two standard deviations from the center in each direction (2 major/minor axes).

- GPU rasterizes these triangles for us.

- Pixel/Fragment Shader

- Using the pixel’s local position in the quad (which is already normalized by the standard deviation in each direction), calculate the alpha value of the gaussian at that pixel, and then alpha blend the gaussians color onto the render target.

Our finished GS renderer runs at a smooth 120 frames per second, and produces the same visual results as [16]. We also allow for keyboard and mouse input for camera movement and rotation, and provide a file opening menu to easily open different files. With the GS renderer completed, the mesh renderer was very simple to implement as we already had the DirectX setup completed. Since the GPU handles the triangle rasterization for us, all we had to do for the mesh renderer was:

- Initialize windows app and DirectX

- Parse the input .OBJ file into vertex and index buffers to load onto the GPU

- Write simple diffuse lighting vertex and pixel shaders

- Tell DirectX to draw the indexed triangles and present the result to the screen.

|

Example render result

Results

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

Our Publicly Released Github Repos

- Splat Renderer: https://github.com/ryanfsa9/Splat-Renderer

- Complete Video to Mesh Training Pipeline: https://github.com/alpergel/final-project.git

References

Depth Anything V2

Yang, Lihe, Bingyi Kang, Zilong Huang, Zhen Zhao, Xiaogang Xu, Jiashi Feng, and Hengshuang Zhao. “Depth Anything V2.” NeurIPS 2024 Poster, 25 Sept. 2024, https://openreview.net/forum?id=cFTi3gLJ1X. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}Segment Anything (SAM)

Kirillov, Alexander, Eric Mintun, Nikhila Ravi, Hanzi Mao, Chloe Rolland, Laura Gustafson, Tete Xiao, Spencer Whitehead, Alexander C. Berg, Wan-Yen Lo, Piotr Dollar, and Ross Girshick. “Segment Anything.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2023, pp. 4015–4026. :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}GS2Mesh

Wolf, Yaniv, Amit Bracha, and Ron Kimmel. “GS2Mesh: Surface Reconstruction from Gaussian Splatting via Novel Stereo Views.” ECCV 2024 Poster, 2024, https://gs2mesh.github.io/. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}FoundationStereo

Wen, Bowen, et al. “FoundationStereo: Zero-Shot Stereo Matching.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.09898, Jan. 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.09898. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}LangSplat

Qin, Minghan, Wanhua Li, Jiawei Zhou, Haoqian Wang, and Hanspeter Pfister. “LangSplat: 3D Language Gaussian Splatting.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16084, Dec. 2023, https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.16084. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}Gaussian-Splatting-Lightning

yzslab. gaussian-splatting-lightning. GitHub, 2024, https://github.com/yzslab/gaussian-splatting-lightning. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}COLMAP

Schönberger, Johannes Lutz, and Jan-Michael Frahm. COLMAP: Structure-from-Motion and Multi-View Stereo. GitHub, 2024, https://github.com/colmap/colmap. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}GLOMAP

Pan, Linfei, Dániel Baráth, Marc Pollefeys, and Johannes L. Schönberger. “Global Structure-from-Motion Revisited.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20219, Jul. 2024, https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.20219. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}Direct3D 11

Microsoft. Programming Guide for Direct3D 11. Microsoft Learn, 2019, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/direct3d11/atoc-dx-graphics-direct3d-11. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}IsoOctree

Kazhdan, Michael. “Unconstrained Isosurface Extraction on Arbitrary Octrees.” Symposium on Geometry Processing, 2008, https://www.cs.jhu.edu/~misha/Code/IsoOctree/. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}OpenCLIP

Ilharco, Gabriel, et al. “OpenCLIP.” Zenodo, Jul. 2021, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5143773. :contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}Taming 3DGS

Mallick, Saswat Subhajyoti, Rahul Goel, Bernhard Kerbl, Markus Steinberger, Francisco Vicente Carrasco, and Fernando De La Torre. “Taming 3DGS: High-Quality Radiance Fields with Limited Resources.” SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Conference Papers, Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1145/3680528.3687694. :contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}SiftGPU

Wu, Changchang. “SiftGPU: A GPU Implementation of Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT).” GitHub, 2007, https://github.com/pitzer/SiftGPU.git. :contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}GS Paper Kerbl, Bernhard, et al. 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering. ACM Transactions on Graphics, vol. 42, no. 4, 2023, Article 1912. Association for Computing Machinery, https://doi.org/10.1145/3592433

GS Math Paper Zwicker, Matthias, et al. EWA Volume Splatting. Proceedings of IEEE Visualization 2001, edited by Thomas Ertl, Klaus I. Joy, and Amitabh Varshney, IEEE Computer Society, 2001, pp. 29–36.

WebGL GS Viewer antimatter15. splat. GitHub, 2025, https://github.com/antimatter15/splat.

Contributions

Automatic Video to SFM to Gaussian Splatting: Alper

Semantical Segmentation: Siyuan & Sihan

Stereo Matching: Alper

Mesh Recon: Siyuan

GS & Mesh Viewer: Ryan